The problem with problems

A quick thought about the disconnect between how we prepare kids for work and how work actually operates:

In school, problems almost always are clearly defined, confined to a single discipline, and have one right answer.

But in the workplace, they’re practically the opposite. Problems are usually poorly defined, multi-disciplinary, and have several possible answers, none of them perfect.

Are timed, standardized tests the way to ready youngsters for real-world problem-solving?

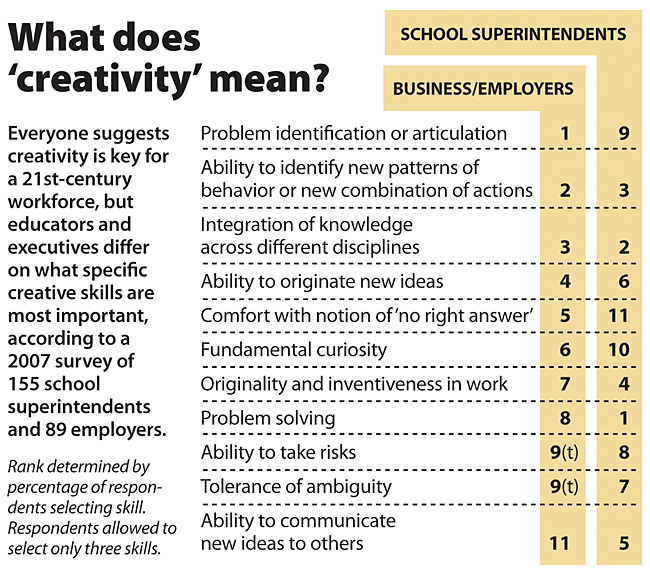

Business leaders seem to think otherwise. Look at the chart below, drawn from research done by the AASA and Americans for the Arts, about how employers and school superintendents (who might have the hardest jobs in America –Ed.) define “creativity.” There’s a fair bit of alignment — but employers seem more concerned with how employees can frame problems and whether they’re comfortable with the absence of a “right” answer.

With TED 2009 coming up next week… a great past TED presentation by Sir Ken Robinson on this very topic of how our schools kill creativity.

http://www.ted.com/index.php/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity.html

Does that mean work is starting to imitate life?

I agree with Sir Ken Robinson’s talk on TED about schools killing our children’s creativity.

As it relates to your post, how would schools/educators be able to measure or grade a student’s success and accept ambiguity? Wouldn’t that be interesting? It would blow the grading curve!

Great study to post. Thanks. I have to delve into the original studies.

Research on cognitive development in young people asserts a general progression from dualism (black and white, right and wrong answers), to relativism (there are no right answers so no worries) and finally to commitment in relativism (some answers are better than others and here’s how I defend my choice).

I studied all that long ago in grad school, but can’t remember if you can reach the final stage without working through the earlier ones, or the implications of introducing ambiguity to individuals in the dualism stage of development. I basically recall that too much ambiguity introduced too soon causes learners to shut down and disengage from learning.

Business leaders would be correct…we need to be teaching our children AND even adults the ability to problem solve. There is no set right or wrong outcome, a solution which may be good for one problem may not be viable for another.

There is a lot of literature on Problem-based learning and is most definitely on the minds of educators, educators who believe in this type of teaching and learning. There are still a lot of educators who believe in the tried and true method of rote learning, standardized testing.

Learners (the future workforce) needs to be able to remember, understand, analyze, apply, and create solutions to all types of real world situations.

So, to answer your question…Are timed, standardized tests the way to ready youngsters for real-world problem-solving?

NO.

Here is a great article emphasizing the need to educate our students differently…

http://www.thejournal.com/articles/23872

It’s interesting the business leaders rank identifying a problem as number 1 and problem solving as number 9, but educators rank the two skills almost exactly opposite. What would a curriculum that stressed problem identification look like?

Re: Cheryl’s question: What would a curriculum that stressed problem identification look like?

An educator could incorporate case studies into the curriculum where learners would need to first IDENTIFY the problem…(a rubric could be developed to assist the learner in what to look for in identifying problems i.e. questions to ask, cues to look for, etc.), then as a collaborative effort, work through developing a solution.

Not only is identifying a problem critical to real world applications, but working as a team, collaboratively is essential as well.

As a college professor, creativity, especially as it relates to problem setting (quite the opposite to problem solving) and the notion of ‘artistry’ as discussed by Schein in his book, “the reflexive practitioner” are incredibly hard to come by. Blame it on the testing, on the schooling, on the lack of time parents have, something is wrong here. Not only that, but studies on gender and education suggest that assignment structure (as in the more detailed instructions, tell me what you want kind of worksheets) favor feminine styles of learning over more masculine. That is, boys seem to do better with the more ambiguous assignment. Which poses an interesting question == if employers favor problem setting, and vague task orientations, and we educate for problem solving and detailed assignments, who are we doing a disservice to and when?

Most companies don’t want just a creative solution; they want a creative solution that doesn’t violate established policy or procedure.

Creative worker are not valued because the act of creation creates change and change is ALWAYS disruptive. It’s only the unusual business that doesn’t treat change in the same way that the body treats an infection.

Re. Cheryl, Heather, Kirsti

According to Tom Kelley, we should throw in some antropological skills in the curriculum.

He was on one of our events recently and talked about the importance of people that could identify a problem to solve for all the engineers.

He calls it a sense of Vuja De…

check out:

http://www.flandersdc.be/vujade

I think the different emphasis that educators vs. business people put on communication of an idea is interesting. First, why wouldn’t business think communicating an idea is important? Second, my experience with the schools so far is that there is an attempt being made to teach expository writing, but I’m not convinced of how well it’s going, especially given the culture of school in which there IS a right answer (reflected here in the #11 ranking of “comfort with no right answer” by the educators). There is a need for educators to learn how to communicate to students when there IS a right answer and when there is not, and to give constructive feedback in the latter circumstance (i.e. asking questions rather than corrections or opinions).