Why progress matters: 6 questions for Harvard’s Teresa Amabile

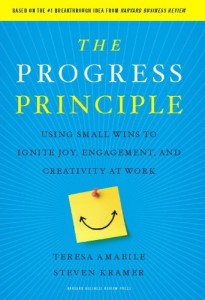

Here’s a tip for rounding out your summer reading. Pick up a copy of The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. The book, which pubs today, is one of the best business books I’ve read in many years. (Buy it at Amazon, BN, or 8CR).

Here’s a tip for rounding out your summer reading. Pick up a copy of The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. The book, which pubs today, is one of the best business books I’ve read in many years. (Buy it at Amazon, BN, or 8CR).

The authors — Harvard B-school professor Teresa Amabile and developmental psychologist Steven Kramer (yep, they’re married) — explored the question of when people are motivated and engaged at work.

And to do that, they took a rigorous and painstaking approach. They recruited 238 people across 7 companies — and each day sent these folks a questionnaire and diary form about their day. Twelve thousand diary entries later — you read that right: Amabile and Kramer amassed 12,000 days worth of data — they reached a set of fascinating conclusions.

Chief among their findings: People’s “inner work lives” matter profoundly to their performance — and what motivates people the most day-to-day is making progress on meaningful work.

I asked Amabile if she’d answer some questions for Pink Blog readers about her book and her insights. You can read the interview below. You can also talk to her live later this month on the next episode of Office Hours.

***

Lots of business books talk about the need for bold, audacious goals — and deride those who “think small.” But your book, which is based on research far more rigorous than its counterparts, takes a different stance. You emphasize the power “small wins.” Why are those so important in the performance of individuals and organizations?

Try to remember the last time you – or anyone you know – had a truly enormous breakthrough in solving a problem or achieving one of those audacious goals. It’s pretty hard, because breakthroughs are very rare events. On the other hand, small wins can happen all the time. Those are the incremental steps toward meaningful (even big) goals. Our research showed that, of all the events that have the power to excite people and engage them in their work, the single most important is making progress – even if that progress is a small win. That’s the progress principle. And, because people are more creatively productive when they are excited and engaged, small wins are a very big deal for organizations.

In addition to examining 12,000 daily diary entries from workers, you also surveyed a few hundred leaders — from CEOs to project managers — about what they think really motivates employees. What did you find out?

Our survey showed that most leaders don’t understand the power of progress. When we asked nearly 700 managers from companies around the world to rank five employee motivators (incentives, recognition, clear goals, interpersonal support, and support for making progress in the work), progress came in at the very bottom. In fact, only 5% of these leaders ranked progress first – a much lower percent than if they had been choosing randomly! Don’t get me wrong; those other four motivators do drive people. But we found that they aren’t nearly as potent as making meaningful progress.

Along those lines, many bosses believe that best way to ensure top performance is to keep their charges on edge — hungry and a little stressed-out. But you found something different. Explain.

If people are on edge because they are challenged by a difficult, important problem, that’s fine – as long as they have what they need to solve that problem. But it’s a dangerous fallacy to say that people perform better when they’re stressed, over-extended, or unhappy. We found just the opposite. People are more likely to come up with a creative idea or solve a tricky problem on a day when they are in a better mood than usual. In fact, they are more likely to be creative the next day, too, regardless of that next day’s mood. There’s a kind of “creativity carry-over” effect from feeling good at work.

Yet negative events have a more powerful impact than positive ones. Why?

We were pretty shocked to discover the dominant effect of negative events on inner work life – people’s mostly-hidden emotions, perceptions, and motivations at work. Setbacks have a negative effect on inner work life that’s 2-3 times stronger than the positive effect of progress. When we checked into whether other researchers had found something similar, we learned that it’s a general psychological effect; “bad is stronger than good.” The reason could be evolutionary. Maybe we pay more attention to negatives, and are more affected by them, out of self-preservation. So – because positive inner work life is so important for top performance, leaders should do whatever they can to root out negative forces.

I was especially intrigued by your findings about time pressure. Sometimes it helps; other times it hurts. Tell us what you found.

The typical form of time pressure in organizations today is what we call “being on a treadmill” – running all day to keep up with many different (often unrelated) demands, but getting nowhere on your most important work. That’s an absolute killer for creativity. Generally, low-to-moderate time pressure is optimal for creativity. But we did find some instances in which people were terrifically creative under high time pressure. Almost invariably, it was quite different from being on a treadmill. Rather, people felt like they were “on a mission”— working hard to meet a truly urgent deadline on an important project, and protected from all other demands.

What are one or two specific things individuals can do to improve their inner work lives and increase their chances of making progress on meaningful work?

Religiously protect at least 20 minutes – and, ideally, much more – every day, to tackle something in the work that matters most to you. Hide in an empty conference room, if you have to, or sneak out in disguise to a nearby coffee shop. Then make note of any progress you made (even if it was a small win), and decide where to pick up again the next day. The progress, and the mini-celebration of simply noting it, can lift your inner work life.

What are one or two things bosses can do to re-architect the workplace and its policies to put progress at the center?

Bosses can religiously protect at least 5 minutes, every day, to think about the progress and setbacks of their team, and what enabled or inhibited that progress. The daily review should end with a plan to do one thing, the following day, that’s most likely to facilitate progress – even if that progress is only a small win. I think this practice, if used widely, could make a real difference in organizational performance and employee inner work life. And good inner work life isn’t only a matter of employee retention or the bottom line. It’s a matter of human dignity.

So, how do we get upper management to buy in to this? It seems like there’s an unwritten rule that workers must be miserable to perform.

So, we all run around (on the treadmill) not really getting anything accomplished yet we’re at each others throats. It’s such a paradigm shift in thinking, regardless of the overwhelming evidence, that it will take decades to change.

Personally, I blame the cubicle inventor 🙂

Thanks for recommending the book, I ordered it up after the ‘Office Hours’ discussion you had with Bob Sutton. The book is very good.

I was actually a little surprised the book didn’t include Mother Teresa’s quote “Be faithful in small things because it is in them that your strength lies.” (http://bit.ly/pf5l6c) I thought it would fit in quite perfectly, especially in these times.

I understand that fear and pressure are over used and that positive motivators make for more pleasant discussions, but these are difficult times, and to pretend that there’s no pressure to preform or reason to be concerned misses an important reality. This is a difficult economy and prudent business policy dictates that one ought to plan on operating with lower revenues for a good amount of time.

I agree with what you wrote in Drive about motivation and especially what “The Progress Principle” identifies as intrinsic motivation. However, one shouldn’t underestimate how little fear clarifies what people should be motivated to do and keeps them on track.

Andy ‘Canoga Park’ Meyer

I don’t know what it is, Dan, but you know how to motivate people to do something.

I want to stop everything and read this book right now. It makes complete sense.

I think the key will be finding ‘meaningful projects’ for each individual to get excited about. In a large corporation, there are so many things that need to be done to keep the machine going that aren’t necessarily exciting ‘change the world’ type efforts. We still have to process the TPS reports.

But there are always things to do to make things better, so if people can get out of the rut of the things they ‘have to do’ and work on things they ‘want to do’, even if it’s just for 20 minutes a day like the authors recommend, then it’ll hold them over to get through the stuff that isn’t so fun.

Thanks for the recommendation.

Bravo for this book! It totally supports the conclusions of my research from a scientific point of view. As business grows in complexity, we must support and empower our teams to collaborate and unleash the wisdom of the organization. This is best understood through the study of chaos theory and quantum physics. Empowered teams are much more adaptable which creates a competitive advantage. I detail this in my latest book, Business Intelligence Success Factors (Wiley/SAS 2009)

The small wins should be the ones we bring up more often. You don’t master something overnight, even if there is a ground breaking invention or theory it didn’t happen overnight but over a lifetime usually.

I would hope that we recognize practice and chipping away more today because everyone can relate. You have better odds of attempting to start a few failed small businesses over a lifetime than you do winning the lottery.

I’ve found that the most difficult thing to bring up is not the validity of data (as this book seems to offer), but instead the actual changes that are required in corporate culture in order to move meaningful change forward. I have approached multiple people at the (engineering) company I work at with the ideas you present in Drive, Dan. It’s always head nodding and agreement with the principles; but when I ask if there can be any action, it’s always “we can’t afford it”. I maintain that companies can’t afford not to do it.

Thanks for the book rec, I clicked “Buy” on Amazon right after I read you saying it was the best business book you’ve read in years. That’s enough for me to check it out!

I need thoughts and ideas about how to relate the ideas put forth in books like The Progress Principle to teachers work environments. Teachers can’t leave the building, and have basically no time during the day to think creatively. At the end of the day, by the time you plan for the next day, attend meetings etc. you are too exhausted to be creative. How can all the wonderful ideas in the business books (besides Drive which relates ideas to teaching)be modified for teachers?

Brilliant. Can be applied to families and other units as well. Thanks for sharing.

Great interview. I echo Jan’s (#7) request for more teacher related ideas, but have to politely disagree with “we have no time for creativity.” As a teacher I would say first, you are being creative much more often than people in other professions. I don’t mean that to deride other jobs, but depending on your subject area you are essentially putting on a show of sorts many times a day. A performer must be exhausted; you are a performer that is charged with educating. I also think if you look closely at your day there is 20 minutes for yourself. Skip out on a negative talk lunch, get to school 20 minutes earlier, stay 20 minutes later if creativity is important to you. The time you might need isn’t necessarily creative time, it’s Jan time just to breathe and decompress. That mental rest is probably as important or more than saying “I need a 20 minute block to be creative.”

Dr Amabile’s comments on being over stressed and the disproportionate impact of negative events….and the power of reflecting on it, and working through it in order to make progress and move forward, reminded me of this writing by amazing Bohemian-Austrian poet, Rainer Maria Rilke: ” “It seems to me that almost all our sadnesses are moments of tension, which we feel as paralysis because we no longer hear our astonished emotions living. Because we are alone with the unfamiliar presence that has entered us; because everything we trust and are used to is for a moment taken away from us; because we stand in the midst of a transition where we cannot remain standing. That is why the sadness passes: the new presence inside us, the presence that has been added, has entered our heart, has gone into its innermost chamber and is no longer even there, – is already in our bloodstream. And we don’t know what it was. We could easily be made to believe that nothing happened, and yet we have changed, as a house that a guest has entered changes. We can’t say who has come, perhaps we will never know, but many signs indicate that the future enters us in this way in order to be transformed in us, long before it happens. And that is why it is so important to be solitary and attentive when one is sad: because the seemingly uneventful and motionless moment when our future steps into us is so much closer to life than that other loud and accidental point of time when it happens to us as if from outside. The quieter we are, the more patient and open we are in our sadnesses, the more deeply and serenely the new presence can enter us, and the more we can make it our own, the more it becomes our fate.”

— Rainer Maria Rilke

Thanks for the recommendation, Dan. I look forward to reading this in depth, though I’ve read some of her highlights on HBR. I wrote about those saying:

Meaningful work and a sense of value within the organization are indeed powerful elements of employee engagement. All work is meaningful and valuable (otherwise, why would you be paying people to do it). The trick is for management to help employees see that meaningfulness and personal value, especially during this tough economy and often stressful workplace environment.

Managers cannot rely on old-school recognition practices of Years of Service, Employee of the Month, President’s Club and similar to achieve this. Such programs only recognize results (or, in the case of YoS – ability to not leave). Rather, employees must focus much more on progress along the way – celebrating the behaviors, achievements, etc., that end up delivering the major successes. In today’s world of projects that can last 2-5 years before final completion, celebrating progress critical.

I’ve written more about this here: http://www.recognizethisblog.com/2010/09/removing-obstacles-progress-recognition/

Hey Dan read and loved your books and I stumbled across a site you will love.

http://www.peopleforgood.ca

I never can get my head around the idea that some companies think getting people stressed out is good management. Sure, there is the idea that they’ll be pushed to work hard and rise to the challenge. But what ultimately happens is that people get on edge, end up looking after only themselves and not the good of the team, and be so tense anticipating what will come next that they won’t be much good at what they’re supposed to be doing in their jobs.

The principles behind this share some similarities with the concept of Rapid Results that is gaining momentum in the international development community. The idea there is to use small victories to make progress (and create a sense of enthusiasm and ownership in the process) without trying to do everything in one big project. “Not changing the system, but not being beaten by the system,” to paraphrase some of the developers. It’s always interesting to see the overlaps between the private and public sectors.

This makes so much sense. People need time (chrono time and mind time) to focus. At last people are realizing that multi-tasking does not produce the intended results. I believe that it delays progress. With this Dan’s writing, you are able to focus for a blocked time on one thing. Excellent. And celebrate the milestones instead of always feeling “not there yet.”

As an engineer, I find that having an engineering problem is more energizing than not. However, it’s the little frustrations that go along with getting things done (whether, it’s “It costs too much.” or I can’t get a software release to build) that saps the energy out.